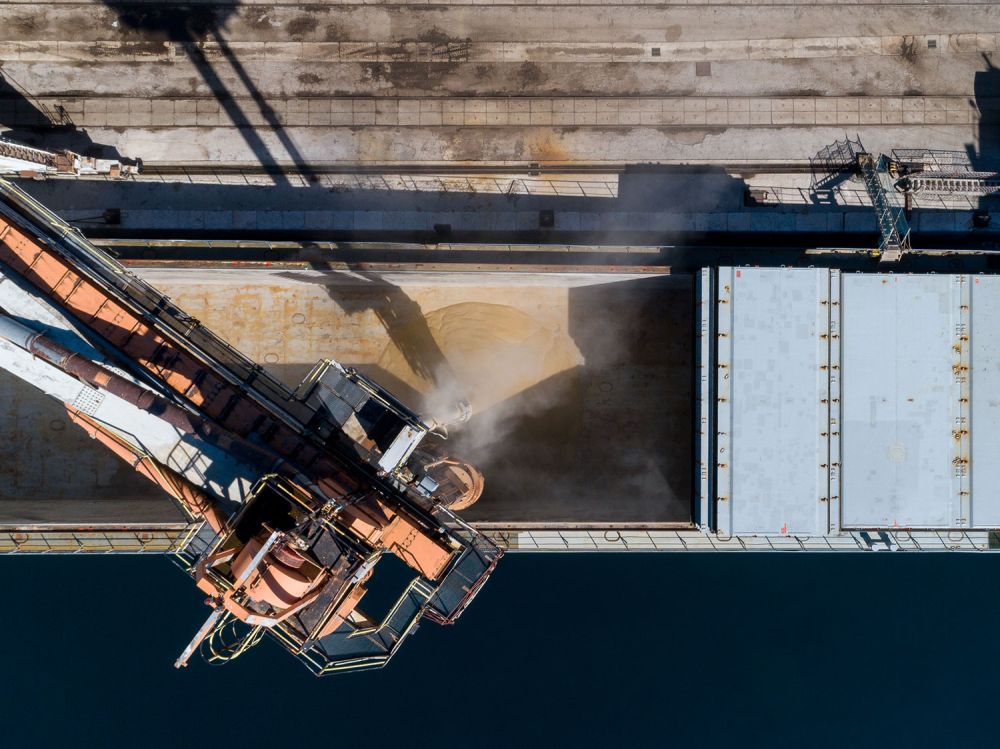

With its fertile soil, Ukraine has long been known as the breadbasket of Europe. Ukrainian ports transloaded up to 30 million tons of grain in 2022 despite the ongoing Russian aggression in its territory. In 2023, the grain crop is estimated at 56.4 million tons, an increase of 2% compared to 2022 but significantly lower than 86 million tons in 2021.

The story is known to many: Until the invasion of the Russian army, Ukraine was capable of handling the export on its own with its extensive fleet of broad-gauge wagons and sufficient port infrastructure. It is like Canadian railroads work when getting their grain from the prairies to the ports on the West Coast for exports. The critical role played the port of Odesa, but grain and oilseeds were exported via Mykolaiv, Yuzhny, Chornomorsk, Ochakiv, Mariupol, and Berdyansk ports. With the Black Sea route blocked, reopened, then stopped again and with port infrastructure bombarded, Ukrzaliznytsia (UZ) cannot count on getting their grain to key customers anymore. Among them are China, Spain, Turkey, Italy, Netherlands, Egypt, Bangladesh, Israel, Portugal, India, Libya, Kenya, and Indonesia. So, all eyes turned to transport by land – where railways are an unbeatable option for getting large quantities of cargo to the alternative ports. According to the latest data, UZ loads between 1.1 (Sept 2023) and 1.5 (Oct 2023) million tonnes of grain into its wagons. The question is where to move them for unloading.

The challenges of grain export by rail

Any other option but direct sea export is not directly competitive. Ukrainian 1,520 mm broad gauge railway ends at its western borders, and grain needs to be transloaded into standard European 1,435 mm gauge. Although some lines in Moldova and Romania run with a broad gauge to the water, it is not directly to the sea, just to the Danube River, where transloading to river barges and another transhipment to larger sea vessels in seaports is needed.

Dry ports at the border of the EU and Ukraine had never seen large quantities of grain transhipment before the war. They were built for bulk cargo such as ores, coal or metal products, with fertilisers and other cargo as secondary. Since the outbreak of war, many facilities have been adapting, changing and amending to make this possible. Not to mention the transloading to sea vessels in final ports, where the infrastructure was not ready for the sudden influx of grain.

Once past the border, the question is the routing. Ukraine has dedicated its exports to two main routes: Poland to its ports in the Baltic Sea and Romania to its ports in the Black Sea. None of these was seamless, and several alternatives (described below) are popping up.

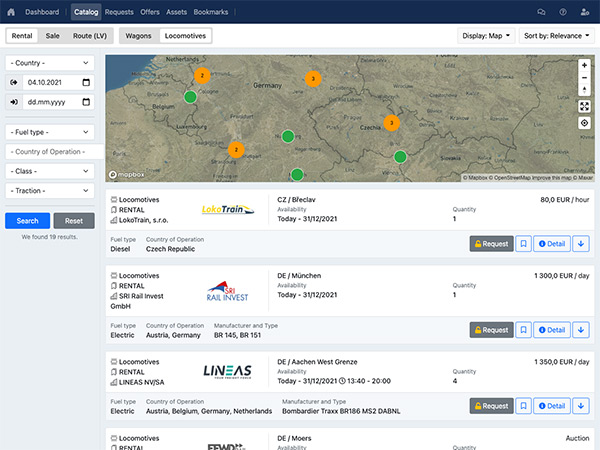

A bigger problem appeared to be on the rolling stock side. Standard gauge European railways do not have enough wagons to transport grain. So, let’s stop here for a while and see the freight wagon options for hauliers in the EU.

Wagons for grain transport in Europe

The golden standard for grain haulage these days is the Tagnpps-type wagon. Tatravagónka, as well as Greenbrier, make them. These 4-axle wagons can take 95 (Millet, Ermewa), 101, 102, 103, 110 (Transcereales), as well as 130 m3 (VTG) of cargo. Large grain wagon fleets are owned by Ermewa, VTG, GATX and Wascosa – the big four in European wagon rental. They were mostly used for exports from CEE (Romania, Hungary, Poland) to North and Adriatic Sea ports by the Ukrainian export needs.

There are several other options for 4-axle wagons:

· Tagnooos 90 m3 made by Greenbrier

· Tadgs 85 m3 used by DB Cargo

· Tads (45, 66 or 80 m3) used by DB Cargo, ZOS Zvolen, or Lokotrans

· Tadgs 85 m3 used by Interfracht

· Tadns 80 used by ÖBB, as well as 82 and 90 m3 made by Duro Dakovic and Tatravagónka

· Tadds used by SŽ tovorni promet, HŽ Cargo (66 m3), and DB Cargo (80 m3)

· Uagpps 123 m3 used by Transcereales

· Uagps 94 m3 used by Ermewa, Interfracht, and Transcereales

Among the less favourable, mostly for their low volume of capacity, are the 2-axle wagons in some fleets, which could be potentially used but definitely not as a primary option:

· Tds (38 m3) – DB Cargo, Rail Cargo Group

· Tdgns (38 m3) – ZSSK CARGO, ČD Cargo

Containers for grain exports?

Using containers for exporting grain is not as efficient. Still, it is a viable option – especially if the end customer takes the cargo in the container in the receiving country and uses it to get the grain up to its facility to unload. In Australia, for example, 13% of grain is exported in sea containers.

ČD Cargo has, for example, used 30’ Upline bulk containers for moving grain between Veľká Ida in Slovakia to Hamburg port.

Big bags and Ea wagons

Several Polish and Slovak carriers also tried an alternative of using Ea-type wagons and big bags to use the excess capacity of these types of wagons. However, this has also not been utilised on a large scale. With big bags, for example, the issues with their strength and instability of load inside loaded wagons led to the minimisation of these transports.

Ban on imports

Previous efforts to move grain west by rail have also led to unintended consequences, with some of the grain being sold in neighbouring Poland and Romania. This led to farmers in those countries complaining they were being put out of business because of cheaper Ukrainian grain flooding the market. The Polish, Bulgarian, Hungarian, Slovakian, and Romanian governments resolved this by effectively banning the sale of Ukrainian grain in their countries while simultaneously assisting with transit by rail to ports to export the grain. This approach is not universally popular with Ukraine (which would be happy to sell the grain at the first opportunity) or the European Union (which, in theory, controls trade policy within the bloc). But it appears to be a pragmatic solution, meaning grain can leave Ukraine and be shipped worldwide, especially to African countries that rely on imports for their grain supply.

While the situation evolves by the day, the five countries imposing a ban have asked for its extension by the end of 2023.

Routes and hauliers for Ukrainian grain export

Two large, fast-growing European economies in the CEE region are also battling to be the primary Ukrainian grain exporters. Poland seemed to play a dominant role at the beginning of the conflict. Still, with the ban on Ukrainian grains, which ended up in CEE instead of just transiting it, Romania is often mentioned as the main partner. There are several other routes, though.

In fall 2023, several states have declared their willingness to help with exports. Lithuania is opened for a Baltic route, using Klaipeda port and unused rail infrastructure in Baltic countries. The problem is that Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia use the same gauge as Ukraine, but Belarus is in the way. So the goods need to be transloaded to standard gauge and to broad gauge again before unloading to ships.

In line with Solidarity Lanes development, the Slovakian route has been discussed to connect its eastern border transhipment terminals with the Italian port of Trieste. Similarly, a Hungarian route can be used, alternating transports to various Adriatic seaports.

Let’s have a closer look into individual countries and their grain carriers:

Poland

From hero to zero – that can be the definition of Ukrainian grain in Poland. Due to disputes with Polish farmers who protested against cheap grain flooding their market, the potential set by Polish authorities for Polish ports to transship up to 10 million tonnes, the numbers in how much grain is moved from Ukraine fluctuate broadly.

Poland is the third biggest grain producer in the EU, producing an average of 34 million tonnes. Six to eight million tonnes out of it go for export. Grain on Polish railways quadrupled from 2021 to 2022, reaching 4.1 million tonnes. The situation in fall 2023 is way more quiet.

PKP LHS is the biggest partner for transport, with up to 12 trains a day. It uses the broad-gauge line from Hrubieszow crossing to Slawkow terminal or Izow to Wola Baranowska. The broad-gauge line leads almost to the Katowice area, which helps with a better turnover of wagons on standard gauge.

In addition, LTG Cargo uses this line for the Baltic route – with trains running from LHS terminals to Traniškiai border crossing with Lithuania to move to broad gauge to the Port of Klaipeda for transloading to ships. For this purpose, LTG also used the principle of detaching the wagon and changing the bogies.

With almost 700 T-type wagons, PKP Cargo is a natural partner for grain exports, while it has by now been the haulier of Polish grain for exports. PKP Cargo and UZ declared the willingness to form a JV for these shipments, which has not materialised. Instead, UZ Cargo Poland was founded, which already sent around ten containerised trains from Odesa-Lisky, Dnipro-Lisky and Vinnytsia stations to the Polish ports of Gdansk and Gdynia.

Another company that is strong in grain bulk shipments in Poland is Freightliner PL, which is still focusing on the stable business of hauling Polish grain to Germany and other Western European destinations.

Among other companies moving grain in Poland, there are Captrain Polska, CTL Logistics, LTE Polska, and Olavion. Laude Smart Intermodal is another player, using containerised shipments and its transhipment terminal on LHS in Zamosc.

Romania

With daily transhipment exceeding 100 wagons, Romania is the next big hope for Ukraine to secure its exports of cereals and oilseeds. Port of Constanta is currently (Oct 2023) the largest exporting route for grain, including imports by river barges, road and rail. Port of Galati might have both standard and broad gauge connectivity, but that stumbles upon lack of motive power on the Moldovan side.

Romania aims to be able to transfer up to 4 million tonnes per month – about 50% of Ukraine’s needs. To boost this, the EU is providing a 24 million EUR package.

Among the players, CFR Mafra, as the incumbent operator, is the natural first choice for many, as the company is used for exporting Romanian crops abroad (Romania is 4th biggest grain producer in the EU). Here, another problem arose when the company leased most of its wagons to export Ukrainian grain. As a result, Romanian exporters have problems exporting their crops this year.

Grup Feroviar Roman (GFR) has a dedicated fleet of around 1,000 wagons, transporting grain from Halmeu, Satu Mare and Dornești, Suceava stations. It takes around 50 hours from Dornești to Constanța, yet the wagons are waiting at the port for unloading for an equal amount of time.

Cargo Trans Vagon is another significant haulier of grain, which comes naturally from the fact that this company is owned by Transport Trade Services (TTS), operating terminals in Constanta.

DB Cargo Romania is also a strong player in moving grain. It has a dedicated fleet of around 400 wagons for this purpose. Among other players in the market, there is, for example, Unicom Tranzit and Constantin Group.

Slovakia

With a daily average of around 60 wagons, i.e. two trains a day, Slovakia is willing to play a bigger role in exporting Ukrainian grain, too. With iron ore transhipment (which has long been a primary commodity for its eastern border transhipment terminals) decreasing, it has stepped up on several fronts.

Interport, a transloading terminal in Košice, has an extensive capacity of 60,000 tonnes per month. The company is building 10,000 tonnes grain silos and elevators capable of transloading 220 tonnes per hour in any weather. It also has a covered buffer storage of 6,000 sqm, which eliminates waiting time for wagons to practically zero.

ZSSK CARGO transported 69,000 tonnes of grain in 2021, whereas in 2023, it already aims for 1 million tonnes. Through its transhipment terminals, BTS, co-owned with Budamar Logistics, can transload 55,000 tonnes of grain per month and has a functional line to pump edible oils from broad to standard gauge system. The transloading is happening on the unused container terminal Dobrá at the moment.

Retrack Slovakia, a JV of VTG and Rail Services Slovakia, is a significant player in grain export from Slovakia. It has a handover agreement with UZ in Čop and Čierna nad Tisou. It runs around a train a day of grain and one train every three days with edible oils, mostly heading towards Germany. For this, it uses 11 Siemens MS locomotives from Beacon Rail and ELL and its own diesel shunting broad-gauge locomotive at the border from Skinest Rail.

LTE Slovakia is another company with a contract with UZ. It can take trains in the same stations as Retrack Slovakia but mostly uses Maťovce border crossing. With around a train a week, it runs trains mostly to Italy and Germany.

EP Cargo reactivated older siding to the thermal plant in Vojany with a direct connection to the broad gauge railway from Ukraine, and it is currently capable of transloading 25-30 thousand tonnes of grains monthly. Its advantage is the ownership of over 300 Tagnpss wagons and the fact that it owns SŽ tovorni promet, a rail freight carrier in Slovenia, which makes deliveries to Adriatic ports for export faster.

Hungary

Hungary is, along with Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Bulgaria, also positioned on the EU Solidarity Corridors. These make a 60% export share, and over 41 million tonnes have been transported so far by these corridors.

The main cross-border transhipment hub is currently Záhony -Eperjeske. The outdated and damaged tracks from the past decades are being restored, and the Hungarian government aims to ensure as much grain as possible can leave Ukraine by rail.

Shipments of grain out of war-ravaged Ukraine are expected to get a boost with the opening of East-West Gate, a high-tech wireless 5G intermodal logistics terminal in Fényeslitke, Hungary. Located in eastern Hungary on the border with Ukraine and Slovakia, the terminal, which launched its operation at the end of October 2023, is expected to handle 800 tonnes of grain and 450 cubic meters of sunflower oil per hour, making it the largest European rail hub for Ukrainian agricultural exports.

Rail Cargo Group moved over 1.5 million tonnes of grain from Ukraine by the end of September 2023. The company takes over the transports at the Dorohusk, Chop and Záhony borders and then transports them further within Europe. Transhipment from broad gauge to standard gauge still takes place in Ukraine. The most common routes for the RCG are from Ukraine to Italy (to traders, as this is where the largest industrial customers are) and from Ukraine to Germany. Due to the scarcity of resources on the southern route, the ports of Rijeka, Koper and Trieste are only served to a limited extent. RCG has arranged to invest in 600 new wagons in 2022. Of these, 200 will still be delivered by the end of 2023 (delivery delay).

LTE is, just like in Slovakia and Poland, also active on the Hungarian market, transporting grain in transit and export. Among other grain hauliers, there is Magyar Vasúti Áruszállító (MVA), Magyar Magánvasút (MMV), FOXrail, or DB Cargo Hungária.

Moldova

Moldovan railways see a resurrection after the need for grain export exploded in the spring of 2021. It moves the cargo via the Novosavițkoe – Cuciurgan crossing. Also, the Berezino - Basarabeasca railway section was opened in Aug 2022. Ukrzaliznytsia participates in the rehabilitation of the Valcinet - Ocnița - Balti - Ungheni - Chişinău – Căinari section, according to a memorandum signed in June with the Railways of Moldova (CFM). In addition, the Bender - Căușeni - Basarabeasca - Etulia - Giurgiulesti is being repaired.

Calea Ferata din Moldova (CFM) is the only rail freight operator in the country, which recently announced the intention to buy new shunting locomotives and freight wagons.

New alternative routes?

In a recent development, the Croatian route was put on a table. Ukraine plans to unload grain from broad gauge to Danube river barges at Izmail and Reni, running upstream to Vucovar in Croatia, transload to trains and deliver it to Rijeka, Split, or Zadar ports.

The most recent development showed yet another option, the Greek route. Greece has offered its ports Thessaloniki and Alexandroupoli for transloading grain after it would move by rail via Romania and Bulgaria.

And last but not least, Montenegro also offered to ship grain from Ukraine through the Adriatic port of Bar.

Many countries express their interest and would like to commit to something that would bring a profitable business to them. Yet, investments in railway lines restoration and modernisation, buying new wagon fleets, and building and modernising terminals – are always about long-term investment.

The insecurities about whether Ukraine would ever go back to its cheapest direct Black Sea route and the question of how long these transports will last make the decision-making in these expensive investments a very hesitant game.